Ásbjôrn cut the stone

3 August, 2015

With this entry I collapse OtRR and let it rest for good.

Last week I read a rune stone text, 28 words or 122 runes. The lix number was 4.37 – how hard can it be? In the two preceding sentences there were 23 words and 81 characters.

Sö 213. Södermanlands runstenar, Sveriges runinskrifter Nybble, Överselö sn. The style is Pr3 – Pr4 (and the stones thus produced in the later part of the 11th century CE).

Runic inscription: s^tain : hiuk : esbern : stintn : at : uitum : bat miþ : runum : raisti : kyla : at : gaiRbern : boanta : sin :· auk · kofriþ : at : faþur : sin : han uaR : boanti : bestr i : kili : raþi : saR : kuni :

In Old Norse: Stein hjó Ásbjôrn, steindan at vitum, batt með rúnum, reisti Gylla at Geirbjôrn, bónda sinn, ok Guðfríðr at fôður sinn. Hann var bóndi beztr í Kíli. Ráði sá kunni.

In Modern English: Ásbjôrn cut the stone, painted as a marker, bound with runes. Gylla raised (it) in memory of Geirbjôrn, her husbandman; and Guðfríðr in memory of her father. He was the best husbandman in Kíll. Interpret, he who can!

For this, and much more information, see Samnordisk runtextdatabas http://www.nordiska.uu.se/forskn/samnord.htm

Relevant parts of Södermandlands runinskrifter, which is an old publication in Swedish, can be found at:

http://www.raa.se/runinskrifter/sri_sodermanland_b03_h04_text_1b.pdf

http://www.raa.se/runinskrifter/sri_sodermanland_b03_h03_plansch_1.pdf

In this master thesis Þórhallur Þráinsson demonstrated that if one wished to design a rune stone arranging the layout in relation to a small number of proportionate circles that also helped the artist draw the contour lines would make it easy to paraphrase a Late Carolingian Iron Age, LCIA, rune stone. The principles were published in a small exhibition catalogue from Museum Gustavianum in 1999 (01). As an experiment a rune stone was produced, painted in the most common CIA colours and put in the university park face up to see what Scandinavian weather in the age of global warming would do to it. This is what it looks like today – the maintenance of rune stones must be included in the commemoration of the diseased.

Since we know about the design methods we shouldn’t read a completely preserved stone like Nybble until its layout has been understood. In this case we must take a small shortcut to understanding by accepting that someone other than the carver had perhaps chosen the stone. What then did it look like to begin with? We don’t precisely know that either because today the stone stands in a private garden partly buried in the ground and not in its original place and position, which was on the nearby Iron Age cemetery.

But if we lift it up and put it down on the ground by means of computer programmes we can make it a blank sheet shadowing its small uneven parts and start the planning:

We know the name of the man who ‘cut’ the stone and this verb is taken to mean ‘designed and cut or carved’. He was called Ásbjôrn or Aesbjorn to OtRR. Aesbjorn would have had in mind the text that was supposed eventually to be fitted into the decoration, and this text was divided into two parts as the Runtextdatabase has it:

A-text: Ásbjôrn cut the stone, painted as a marker, bound with runes. Gylla raised (it) in memory of Geirbjôrn, her husbandman; B-text: and Guðfríðr in memory of her father. He was the best husbandman in Kíll. Interpret, he who can!

Aesbjorn chose a quite common design that would allow these two texts more or less to form a circle, and thus first of all he had to find a centre and a circle to go with them. He gave this main circle a diameter of 48 units (02).

The planning starts in the prime centre (PC) and the carver intends to divide the decoration into an A- and a B-part related to the future inscription. Moreover, he wants there to be an upper, a central and a lower ornamental focus (uf, cf and lf) of the A-part. These three elements are to be based on each their 12-units circles.

The centre of the upper focus, the secondary centre (SC) is situated 17 units above PC. From SC a secondary line defined by a point (SP) 4 units to the right of PC on the horizontal diameter slopes into the A-part of the stone. The upper focus (uf) is the same point as SC and Aesbjorn defines the central focus (cf) as 16 units below uf and defines the lower focus (lf) as an additional 17 units further below uf on the secondary line. This means that the distance between the upper and the central circle is 4 units. Between the central and the lower circle there are 5 units.

The three 12-unit circles aim at balancing the composition and in addition following part of their periphery helps to outline the contours of the key decorative elements. To facilitate the drawing of these elements a number of smaller circles are used, and although some of these may have been fixed by coordinates in the layout there seems to be no point in trying to figure out how.

The smaller inner and outer contour circles in the B-part are there to make the serpent in this part smaller than the A-part animal with its larger circles. The larger circles in the upper part of the stone make the overlapping ‘head bends’ larger than the separated ‘tail bends’, which are kept together by a leash that binds together text and decoration.

The central four-footed animal with its 12/6-unit circle combination is the most impressive of the three key elements and if we think that is body is a bit narrow it is because its breadth equals 4 units.

Finally, the construction of an 8/7-unit pair of circles guiding the small animal’s long ‘crest’ has resulted in ‘constructed’ irregularities.

The composition is based on two united serpent-like animals. Between them and probably bridging them stands the large four-footed animal, which is usually considered to be the Lion of Judah or Christ from the Book of Revelation, 5:5.

If we look at the A- and B-text they are different in a way that matches the decoration. The A-text is the important one, B is more straightforward and dependant on A. The widowed Gylle, the deceased Geirbjorn and Aesbjorn crowd the A-text and they have the lion’s powerful front among them. The B-text relates to Guðfríðr who commemorates her father repeating Gylle’s statement adding that her father was the best of Kil men. In the end she asks the reader to interpret the monument. This last sentence refers back to the beginning of the text since that is where the monument is described by Aesbjorn. Most often carvers mention themselves in the very end of a text – not so Aesbjorn, who proudly declares: Stein hjó Ásbjôrn, steindan at vitum, batt með rúnum … . The database has is:’Ásbjôrn cut the stone, painted as a marker, bound with runes ‘. The transation is correct, but not so faithful to the poet who wrote this part of the inscription as of a strophe. Viti means ‘a marker’, but so does the more frequent word mark and there is more to the word viti. Choosing viti, which is the same word as wit, Aesbjorn wants to make something known in a more manifest or extrovert way and at vitum could be translated ‘to witting’ in the dialectic sense: knowledge or awareness of something. That is why he also uses the verb steinda which means paint, but so does the more common word faði. Aesbjorn chose steinda because he needed an alliteration on stein, but steinda nevertheless has an emphasized element of adding something to something enhancing it as in the term stained glass – to colour, therefore, is a better choice than to paint if we think that stained is too negative. Batt með rúnum means bound with runes referring no doubt to the two-serpent layout carrying the runes. Thus the two first lines of the strophe run:

Stein hjó Ásbjôrn, steindan at vitum,

batt með rúnum, reisti Gylla

Aesbjorn cut the stone coloured (stained) to witting

Bound with runes Gylle raised it

Grammatically, with their insertions these two lines are but an unfinished statement waiting for

at Geirbjôrn, bónda sinn —‘after Geibjorn her husband’ to conclude the strophe.

The whole strophe therefore amounts to:

The first two lines are emphatic and repetitive, but that of course is meant to be contrasted by the less rigid concluding line that includes the strophe’s only anacrusis. From a rhythmic point of view the translation would be better if Geirbjorn was Gylle’s ‘lord’:

Aesbjorn cut the stone, stained to witting,

bound with runes, Gylle raised it

after Geirbjorn her lord.

It’s a Ljóðaháttr statement and the A-text therefore is poetry, the B-text (just) prose, albeit divided into three distinct parts: … and Guðfríðr in memory of her father.| He was the best husband in Kil. | Interpret, he who can!

The database has ‘husbandman’ for bónda, but why Geirbjorn should be a small landower or tenant rather than a yeoman is difficult to say. Bónda would seem to allude to the master of a household. Geirbjorn in his social capacity as a bónda unites the two different texts, the commemorators and the two serpents, which represent a basic divide and unity among those left behind.

I think it is fair to suggest that Ráði sá kunni—‘Interpret, he who can’ alludes to the text :: design relation, that is, ‘the text in interacting tandem with the design’. There are obviously interpretations that we can defend: the two serpents represent Miðgard and its people, among whom there are greater and smaller ones. The Lion of Judah, nevertheless, is there for everybody. So far so good, but when we read the text this ‘decorative’ meaning is not the only truth. Kil stands out as a miniature Miðgard and when a person dies the diseased belongs to the whole of Kil/Miðgard, the A- and B-text respectively, protected by Christ on doomsday. This kind of interactive interpretation will soon become guesswork only, albeit perhaps true, and that I think is the reason why ráði sá kunni—‘Interpret, he who can’ has been chosen as a conclusion. Checking the number of syllables and the meaning of words as well as the size and position of circles is not enough

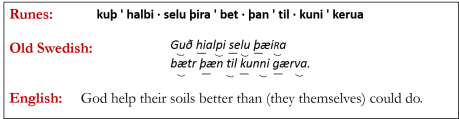

Before we conclude that every one of us thinks the artist does construct too much, we shouldn’t forget that Aesbjorn added a new kind of metaphor to his verse: (the stone is) steindan at vitum—‘stained to witting’, perhaps it meant something even to the stone – perhaps Aesbjorn had true north on his poetic compass. This is not quite unbelievable since on Selaön of all places the text on a contemporary rune stone Sö 197 ends with a quite common prayer, which nevertheless stands out as singular because it is grammatically transformed and reformulated as the first rhyming pair of qualitative iambic trimeters in Swedish poetry. There’s a new one:

Metaphors and iambic verse – something happened to the poetry on Selaön in the 11th century. ráði sá kunni!

NOTES

(01) See Þórhallur Þráinsson. 1999. The exhibition sketches. In Eija Lietoff (ed.). Rune stones — a colourful memory, pp. 21–21. Museum Gustavianum. Uppsala as well as, Þórhallur Þráinsson. 1999. Traces of Colour. In Eija Lietoff (ed.). Runestones — a Colourful Memory, pp. 21–30. Museum Gustavianum. Uppsala.

(02) Since the greatest height of the carving was 1.36 m and the breadth 1.38 m it stands to reason that the circle was 4.5 foot in diameter and the foot thus ((136+138)/2)/4.5=30.44 cm. The unit Aesbjorn used was 1½ inch.

Childeric was Buried a Son’s Father

13 April, 2015

This week On the Reading Rest I have a print-out of an article from the open access journal, JAAH http://www.arkeologi.uu.se/Journal/

Fischer, Svante & Lind, Lennart 2015. The Coins in the Grave of King Childeric. Journal of Archaeology and Ancient History 14. Pp. 1-36.

Fischer, Svante & Lind, Lennart 2015. The Coins in the Grave of King Childeric. Journal of Archaeology and Ancient History 14. Pp. 1-36.

Fulltext: http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:793693/FULLTEXT01.pdf Acronym: FiLi

In the end of the 1990s it was proposed that the time depth and distribution of coins in a hoard could be compared with that of the names of Kings used in a chronological series to give historical i.e. time depth to a certain context. The series consists of a few old and famous kings and many partly unknown younger ones. The example given was the first series of kings in the poem Widsith, which includes several of the kings mentioned in poetic texts – that is the Finnsburh Fragment and a section in Beowulf – about the hall called Finnsburg. The chronological distribution of coins in hoards could be read as kings’ names and linked to events in the past in similar way as name series. Ten years later is was suggested that a series of weapon could be viewed in the same perspective. When the small hall in Uppåkra, Scania (0) was smashed in the beginning of the 6th century it would seem that a series of weapons were deposited in a waterlogged depression just north of the house. In a traditional weapon offering after a victory this kind the weapons date the battles – each battle forming a chronological peak among the offered military equipment. At Uppåkra nevertheless, the series resembled a long chronological period with a few very old and several younger weapons. Since halls are known to have contained weapons it was thus conceivable that the weapons in the Uppåkra depression were the offered spoils taken from the walls of the hall when it was conquered and smashed.

The idea is simple enough: by collecting a series of objects or names one can create a network that will sustain a historical narrative. The point being that this was done consciously in the middle of the first century CE. Ideas may be interesting, but do the lend themselves to be proved? This is where FiLi comes in.

King Childeric’s grave is a signed installation excavated in the 17th century and immediately understood to be Childeric’s grave because of the signet ring probably found on the finger of the buried person: childerici regis it says referring to what of his he signed with this the king’s ring while alive. The grave installation was soon understood to contain a message respecting the new Byzantine Empire created 476 CE when West Rome disappear. But as FiLi points out the installation is actually ‘signed’ by Childeric’s son Clovis, who used his right as a descendant to design the funeral and burial.

King Childeric’s grave is a signed installation excavated in the 17th century and immediately understood to be Childeric’s grave because of the signet ring probably found on the finger of the buried person: childerici regis it says referring to what of his he signed with this the king’s ring while alive. The grave installation was soon understood to contain a message respecting the new Byzantine Empire created 476 CE when West Rome disappear. But as FiLi points out the installation is actually ‘signed’ by Childeric’s son Clovis, who used his right as a descendant to design the funeral and burial.

During later years earlier interpretations stressing the devout attitude of dependency to the new Byzantine Empire, thought to be symbolized by the Byzantine artefacts on display in the grave, have been questioned and now FiLi sets out to reinterpret the most outstanding objects in the grave: the two hoards (1) the 100 gold coins, 5th c. solidi, of which 89 were described and 12 depicted in the 1655 publication and (2) the 200 silver coins of which four were illustrated. It is FiLi’s combined and numismatic knowledge and overview of the period in question, the late 5th century that allows them incorporate the hoards into a much more rewarding reading of the burial context – the hoards being the most complex messages in the installation.

I’ll concentrate on the gold coins. FiLi shows that originally the coins were collected in the West Roman Empire foremost Italy during the chaotic decades leading up to the fall of Rome 476 CE and Childeric’s death 481/82. Contrary to what one might have expected this didn’t mean that the coins in the hoard were a mirror of the coins that circulated in the West during those years. On the contrary someone (read Clovis) have sorted out the coins that mirror the coinage of the last emperors in the West and opponents of the East Roman emperors. What the gold hoard signals is thus not just King Childeric’s and Clovis’ dependency of Byzantium, but all the more actively a wish to distance themselves from the former West and its last more or less dubious emperors. Clovis wanted to emphasize that the Franks had created the new West. To many, the message of the coins may have been obscure, but as FiLi argues not only Clovis could read the coins, many of the funeral guests would have been familiar with the coin legends.

FiLi’s analysis discloses a sophisticated insight into the mind of Clovis adding a material statement to oral eulogy in what was probably a masterly directed lit de parade and funeral. Moreover, the statement delivered by the hoard is a historical statement summarizing the outcome of a number of turbulent and decisive decades in European history.

Since On the Reading Rest is free to develop analysis a little further, interpreting context in a textual way, it seem possible to add an interpretation to the gold hoard developing its perspective on the past. This interpretation falls within the frames established by FiLi.

*

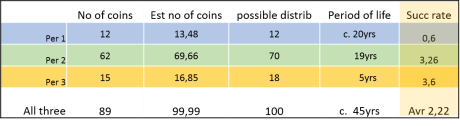

One way of looking at the hoard is to consider of a mirror of Childeric’s life dividing it into phases such as before he became king 457 CE (a period of c. 20 yrs); between that date and the fall of Rome or Childeric’s alliance with Odovacer, i.e. 476 (a period of 19 yrs), and the rest of his life until 481, a period of 5 yrs).

If we divide the coins into these three periods the 89 coins are distributed 12 – 64 – 15, but since they amount to no more than 89% of the coins, the expected numbers are 13,48 – 71,91 – 16,85 respectively. Since 11 coins are missing it is likely that the original composition was (12+0) = 12 – (64+6) = 70 – (15+3) = 18.

The years covered by the periods are c. 20, 19 and 5 years respectively.

The periods covered by the coinage according to legends and types are 431-5 to 456 CE ; 457 to 476 CE and 474/5 to 491 CE.

The start of the last period is a result of the Emperor Zeno’s troubles in the beginning of his reign. That period is mirrored in the sample because it was a Constantinopolitan problem. After 476 CE we may confidently see him as a powerful ruler who died 491 CE. In practice therefore, the emperor who would have been told about the burial was Zeno. What Clovis describes is Childeric’s life in terms of gold coin success as a sign of general success as seen in the above success rate.

This is obviously not bad on the contrary it is a growing success and Clovis saw the life of his father as a period of success irrespective of whether the West Roman Empire existed or not. Since he is depicted as the King of the West and loyal to Byzantium, Childeric did better when he came into power and always well.

It was a success when Childeric became king, and the fall of Rome caused him no trouble.

In addition to the coins as measures of success the collection is also one of names and as FiLi has shown this is its most obvious expression of intent. This should worry the Southeast Scandinavians because some of their most historical coins from this period, collected by themselves in Italy, were issued by the very emperors excluded by Clovis. Everybody may not have been happy with what they when they examined the coins — or rather when they saw what was lacking. The importance of warfare, nevertheless, wasn’t doubted and among his contemporaries, the Gallo-Roman rulers in the domain of Soissons were probably among those who noticed the peculiar lack of western coins in the funeral hoard although these rulers were not defeated by Clovis until 486.

Honouring his father, Clovis sets a new agenda and he doesn’t keep his father’s signet ring as a sentimental object of veneration. Probably he would have explained he decision not to keep it with reference to his father needing in the next world, in which by his funeral definition he seems no more than his son’s father.

NOTE

(0) On Uppåkra in general, see for instance: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upp%C3%A5kra

Helgi Hjörvardsson — Dying to be Reborn

6 April, 2015

This week On the Reading Rest I have one of the less rewarding poetic compositions among the Eddic texts. Usually it is known as Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar—The lay of Helgi son of Hjorvarth. In codex Regius, the only manuscript in which the text exists, it is called Fra hiorvarþe oc sigrlin—On Hjorvard and Sigrlinn and that is a level 2 caption, which designates a primary section within the first or the second part of the manuscript (1).

Since King Hjorvard wants a fourth wife and one more beautiful than the three beautiful ones he already has he sends Atli, the son of his Earl Idmund, together with some men to King Svavner to ask for his King’s daughter Sigrlinn’s hand in marriage. Hjorvard has heard that she is the most beautiful. Of course he wants a son too. He already has three, one with each wife, so why not a fourth. Hjorvard sends out his suitor, as we would expect him to do.

In Svavaland the neighbouring King Svavner’s realm the Earl, Franmar, is also the foster father of the King’s daughter and Franmar advices against the marriage – case closed!

We get the impression that Hjorvard collects beautiful young women and that power in King Svavner’s kingdom is divided in order to curb the king.

One day, before he returns, Atli is standing in a groove listening to a gossiping bird. He strikes up a conversation with the bird, who obviously has information to sell, but while negotiating an agreement the bird gives away the essence of its secrets. Atli understands that Sigrlinn’s consent is in fact not the problem.

Returning to Hjorvard’s court, Atli doesn’t mention his bird talks. Instead he explains his lack of success with reference to the difficult journey over the liminal elements of the world – high mountains and a river separating the kingdoms. Probably Atli and his men didn’t look too good when they arrived at Svavner’s, but their difficulties are just the ones a suitor meets when he sets out to woo on behalf of his master within the model of the Holy Wedding. In this case the differences between the kingdoms could not be overcome.

King Hjorvard suggests that they try again and this time he will join them.

The common reader and indeed King Svavner, not to mention Franmer, will tend to find it odd and threatening that King Hjorvard takes such an undiplomatic step, given that any king could be expected to use force to get hold of Sigrlinn.

Not surprisingly therefore, when the wooing party reaches the top of the mountains and looks down on Svavaland, they see a country plagued by war. It would seem that a certain King Rodmar has killed Svavner and ravaged and burnt the country because he couldn’t have Sigrlinn.

Well in Svavaland in their first camp, Atli, despite being on guard, crosses a river in the middle of the night and hits upon a house guarded by a bird that has fallen asleep. He snipes the bird with his spear, enters and finds Sigrlinn and Alov – what a coincidence! Since this calls for an explanation we are told that because of Rodmar and his warriors, Earl Framnar who had to save his two daughters brought them to this safe house defending them with magic while dressed in his eagle guise. With no father, foster-father to trouble them Hjorvard takes Sigrlinn and Atli puts up with Alov. Since all readers of Eddic texts are supposed to be as conventional as a Wagnerian opera audience with double standards we know that Atle’s raid leaving his duty is wrong, but also model WW1 behaviour: leave your own lines, cross no-man’s-land, snipe a guard, take two prisoners and bring them back.

This concludes the first section of the texts related to Helgi Hjörvardsson. The strophes quoted so far relate to Atli, his bird talking capacity, audacity and cunning behaviour – taking risks and being successful.

As expected Hjorvard and Sigrlinn produces a son, big, beautiful and taciturn. None of the names given to him fasten on him. Then in the stage direction way dialogues are most often introduced in Eddic texts we are told: He sat on a hill. He saw nine Valkyries riding and one was the noblest. She said:

In the small dialogue that follows this Valkyrie calls the boy Helgi. She tells him where he can find a good sword and since the reader hasn’t yet been told in the strophes, this section ends in prose announcing that the helpful Valkyrie is called Sváva, her father being King Eylime.

After this rite of passage when the taciturn teenager becomes a man and adopted by the young Valkyrie, he pulls himself together and criticizes his father for not having stopped Rodmar when Svavaland was wasted. Hjorvard, who seems to be a cunning coward, immediately gives Helgi enough men to revenge his grandfather Svavner. Whatever the outcome when Helgi turns Beowulfian, travelling the country solving problems by killing things, Hjorvard will benefit. Helgi collects the sword, sets out together with Atli, who else, and slays Rodmar. This is the beginning of his great deeds.

So far the persons responsible for making Helgi a man have been presented. The strophes have been no more than interesting quotes of direct speech from epic narratives. The prose on the other hand has created a framework for the poetic fragments.

The next section consists of 19 strophes, a dialogue interrupted by prose, between the evil giantess Hrimgerd, loyal old Atli and capable young Helgi. Touring Norwegian fjords doing their deeds Atli and Helgi have killed the giant Hata a horrible and habitual bride abductor. Afterwards in the night when Helgi, Atli and his men are on board their ship, and Atli keeps watch while the others are sleeping, Hata’s daughter Hrimgerd tries to lure Atli ashore. This time he wisely stays on board and together with Helgi they quarrel with Hrimgerd until it dawns and she, being a troll, is petrified.

In the standard carrier of a mythological king Helgi has reached the point where he has shown good strategic sense on top of bravery, righteousness, good looks and a taciturn childhood. Consequently, Helgi is ready to become a king.

It is obvious that Helgi and Atli, Sváva and Hrimgerd as well as Hjorvard and Hata constitute complementary pairs. The two kings, man and giant, are obviously mostly interested in beautiful young women and of the two young but violent women Sváva is the righteous one while Hrimgerd is the over sexualized monster. The male pair – the old retainer and the young prince – is not unheard of either. There’s a touch of Falstaff and Prince Hal when Atli and Helgi wrangle with Hrimgerd. However, in the process of making Helgi a king, Atli develops from the daring young man who leaves his night watch to the loyal old retainer who doesn’t.

Significantly, Helgi, who must have an H-name like his half-brothers and their father, is called just that: Helgi – the holy one (he who is dedicated to the gods) by Sváva who is the equivalent of a God sent angel. His father the powerful Hjorvard—the sword guardian, moreover, is not as good as Hegli.

The long 19 strophe-dialogue in which Helgi gets the last word, calls for minor epic continuation or why not just another break and a new prose section jumping to the next predictable stop in Helgi’s life.

So, when Helgi passes by King Eylime’ court he asks to marry Sváva and since they love each other they are betrothed. He continues to fight and she doesn’t stop being a Valkyrie. Everything seems prosperous! But then Hedin, Helgi’s half-brother, meets a witch riding on a wolf on Yule-eve. She bauð fylgð sína Heðni—offered Hedin her help, but Hedin just cries out ‘No!’ stupidly giving the witch a reason to get annoyed and curse him. Yule-eve rituals eating pork and sharing a mead cup includes a serious New Year’s resolution, Consequently, Hedin being cursed and bent by magic, vows that he shall gain Sváva for himself. Having sworn, Hedin is devastated by his pledge and seeks out Helgi who is campaigning in the southern part of the country. And we the readers are in for another fragment of a dialogue, five strophes, between Hedin and Helgi.

Super-neurotic Hedin is heartbroken, but Helgi tells him not to bother and explains that since he has a duel coming up they might as well wait and see – fate being fate. And then, clairvoyantly, Helgi tells Hedin exactly what happened on Yule-eve when Hedin met the witch. Since clairvoyant kings are usually more carefully introduced, as in the Finnsburg fragment, this strophe calls for an explanation. In this text explanation is matter of prose and the author goes on to tell us what we expect: In the duel Hegli is lethally wounded by Alf the son of King Rodmar.

The duel took place at Sigarsvoll and Helgi sends Sigar off to fetch Sváva. She comes, Helgi dies and dying he expresses his opinion that Sváva should love Hedin, but Sváva doesn’t think so Hedin being jöfur ókunnan—an unknown prince. Being what he is the ever-vowing Hedin who is present cries out: ‘kiss me Sváva’ before he promises not to return until he has revenged Helgi, the best lord etc. Notably in this scene Sváva is not present to begin with although as a Valkyrie she is supposed to look after her Helgi. On wonders whether her active years were over.

Finally in plain prose we are told that Helgi ok Sváva er sagt at væri endrborin—it is said that Helgi and Sváva were born again. Many poems end in some sort of poetic vein but why elaborate in a text that just wants it readers to know so that they don’t forget.

If ever there was a cut-and-paste author ridden by topoi (cf. On the Reading Rest, Devotional Formula 19 August, 2013) it is the compiler of the Eddic text we call helgakviða hjörvarðssonar. At least two metrically different poems have been cut up and patched together.

Everything is chucked in, the cunning king, the suitor in an echo of the Hieros Gamos myth, the perfect retainer, the bipolar loser-brother, the vicarious parricide on Hata, trolls – wolf-riding as well as petrified, madonna and whore (the filth is in strophes 19-22), the clairvoyant king, curse, vow, fate and the objectified female beauty Sigrlinn. We are not even spared an offer death and resurrection reminding us of Christ’s. There is no Christ, no Easter, no supper, no wine, no Judas, no crucifixion, and no Mary Magdalene. But there is a twist: Sváva, duel, Hedin, beer, pork, Yule and prophetic Helgi.

That Helgi and Sváva are born again is more or less the whole point. The love-driven resurrection story might come in handy if we intend to compose something on the cause and effect of Fimbulwinter and Ragnarök (cf. On the Reading Rest, Codex Regius is a Synopsis, 9 March, 2015).

And would you know! Everything started with Hjorvard – topos: old king with dubious habits, sending off Atli – topos: young man who speaks with birds, to woo – topos: standard upper-class procedure.

It seems that all this happened in Western Norway and in a larger historical perspective this is not a bad setting. Not because the events in the patchwork took place in Norway, they didn’t inasmuch as everything happened in a study defined by its narratives. Fictional Western Norway is suitable a setting because we can imagine that in it intellectuals understood that outside their study they witnessed the interaction between, and the practical transition from a folk-religious society accepting a an autonomous reality demonstrated as fate to a society accompanied by a universal religion, which in principle didn’t accept fate and its consequence an autonomous reality.

NOTES

(1) On the captions and the structure of Codex Regius see:

Lindblad, G., 1954. Studier i Codex Regius av Äldre Eddan i-m. [Lundastudier i nordisk språkhistoria 10.] Lund.

Or more specifically on captions:

Herschend, F. 2002. Codex Regius 2365, 4to – Purposeful Collection and Conscious Composition. Arkiv för nordisk filologi. Vol 117:121-143. http://journals.lub.lu.se/index.php/anf/article/view/11655

A Perfectly Decent 5th c. Hall

23 March, 2015

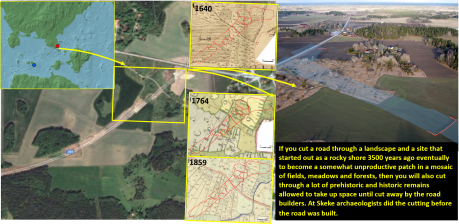

This week On the Reading Rest I have a report from a road section excavated by archaeologists before the road was built.

Larsson, Fredrik et al. 2014. Skeke – gudar, människor och gjutare. Rituella komplex från bronsålder och äldre järnålder samt en höjdbosättning från yngre järnålder med gjuteriverkstad. Utbyggnad av väg 288, sträckan Jälla–Hov, Uppsala län; Uppland; Uppsala kommun; Rasbo socken; Skeke 1:3, 2:6; Rasbo 55:1–2, 654, 655, 669, 695, 696, 697, 626:1–627:1, 682–688 samt delar av Rasbo 628:1 och 629:1 UV rapport 2014:53 Riksantikvarieämbetet. Stockholm.

Larsson, Fredrik et al. 2014. Skeke – gudar, människor och gjutare. Rituella komplex från bronsålder och äldre järnålder samt en höjdbosättning från yngre järnålder med gjuteriverkstad. Utbyggnad av väg 288, sträckan Jälla–Hov, Uppsala län; Uppland; Uppsala kommun; Rasbo socken; Skeke 1:3, 2:6; Rasbo 55:1–2, 654, 655, 669, 695, 696, 697, 626:1–627:1, 682–688 samt delar av Rasbo 628:1 och 629:1 UV rapport 2014:53 Riksantikvarieämbetet. Stockholm.

It is difficult to know what the place name Skeke means, but it could in principle refer to a landscape element characterized by oak trees or less likely contain a word meaning ‘to spread’ (Larsson et al., p. 42 with references). In this entry I shall use the very unlikely but at least pronounceable Spread-Oaks or Spreado for short.

It is difficult to know what the place name Skeke means, but it could in principle refer to a landscape element characterized by oak trees or less likely contain a word meaning ‘to spread’ (Larsson et al., p. 42 with references). In this entry I shall use the very unlikely but at least pronounceable Spread-Oaks or Spreado for short.

All kinds of things are dated at Spreado. 14 C-wise ‘everything’ gives rise to a number of questions and looks like this:

However, if we disregard questions about continuity and discontinuity and filter the dates according to categories some patterns arise.

However, if we disregard questions about continuity and discontinuity and filter the dates according to categories some patterns arise.

Spreado is inaugurated with a grave indicated by the earliest date of cremated human bones. This monument is probably a pre-settlement manifestation although there may of course be some kind of settlement outside the excavated road corridor. For 400 years one burial seems to suffice, but c. 1000 BCE graves start to become more common. Sometime during the 3rd c. BCE this grave period comes to an end. As expected in this kind of ‘cemetery monument’ there are structures that did not contain any burial remains. Perhaps, and in that case typically, there is a small burial-revival during the Carolingian Iron Age (Spreado:55; 65).

Spreado is inaugurated with a grave indicated by the earliest date of cremated human bones. This monument is probably a pre-settlement manifestation although there may of course be some kind of settlement outside the excavated road corridor. For 400 years one burial seems to suffice, but c. 1000 BCE graves start to become more common. Sometime during the 3rd c. BCE this grave period comes to an end. As expected in this kind of ‘cemetery monument’ there are structures that did not contain any burial remains. Perhaps, and in that case typically, there is a small burial-revival during the Carolingian Iron Age (Spreado:55; 65).

The first dwelling house, House 16 doesn’t convince the reader although on can naturally build something makeshift on a random distribution of post holes. Not until the late Bronze Age are there any typical dwelling houses at Spreado. They are just two but in all probability there were many more in the environment owing to the temporary character of the one-house farms of the period. Nevertheless, grains, animal bones and houses covariate although many of the grain finds are intrusions in much later houses build on top of the earlier temporary farms. Spreado is a good example of the Early Iron Age habit of resettling a place that has already been settled albeit hundreds of years earlier.

The situation at Spreado reflects the fact that Late Bronze Age and Early Pro Roman Iron Age living produced a lot garbage that wasn’t moved out of the settlement as well as holes and layers in which to trap garbage and ecofacts. Later settlements at Spreado are not characterized in the same way.

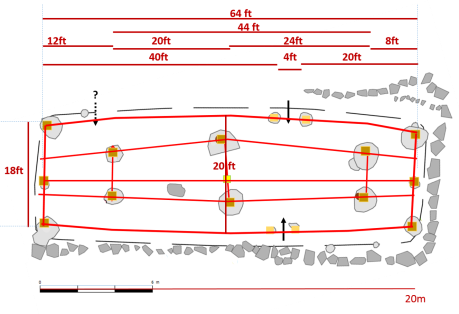

The dates of the dwelling houses at Spreado reveal the expected pattern: a few short dwelling periods during a millennium and then the establishment of a more stable settlement during several hundred years. This often happens before or the beginning of the Common Era, but in Spreado it happens late. The farm, which may at times have had two households, is eventually characterized by a small hall, House 2. The precise date is difficult to give owing to contaminations, but c. 400 CE is a plausible date. The farm on which House 2 is the emblem doesn’t survive the turbulent 6th century. Exactly when House 2 was rebuilt as House 21 is difficult to know since it is dated by an animal bone in a layer. The bone has little precise linkage to the house.

The interesting thing about House 2 is its measures. they are formalized in a way that is characteristic of the end of the Early Iron Age. Although the house may not have been an elegant or well-proportioned building – it was, however, a well-measured edifice, which shares some common South Scandinavian traits and perhaps some sort of architectural norms emphasizing measure and structure rather then function, in a way that would not have suited the general functionalistic norms of the Early Iron Age.

At the same time there are some local characteristics in the post setting and wall height and in the fact that the building was erected on a terrace on top of a small hill in order to be seen from afar. This landscape statement was deemed important because older graves had to be removed in order to give room for the building (Spreado Fig2:6 p:25; p:61ff.).

As an ideological statement, the hall at Spreado is older than the middle of the 6th century and the 536-45 CE dust veil, that is earlier then the new large halls characteristic of Lejre and Tissø. It is in other word a manifestation of the old upper classes, their inter-Scandinavian hall-designing network as well as their wish to prove themselves locally.

The contrast between Gilltuna (On the Reading Rest: 6 October, 2014: 536 and all that – the Gilltuna case) and Skeke is in other words model: Gilltuna, a traditional village closing down in the 6th century, happened to become one of the new large estates of the Late Iron Age characterized by its large 27-metre hall; Skeke, a traditional village formed in the 3rd century, developed into a 5th-6th century estate with a 20-metre hall. Both sites are exceptional: Skeke because it survived long enough to become a hall farm giving us a glimpse of an Early Iron Age success that came to nothing; Gilltuna because it was Late Iron Age success that came to nothing. The two farms happen to mirror something significant: the social change among the well-to-do in the 6th century.

Since the fate of the Spreado hall and events central to Beowulf or Codex Regius as a synopsis (cf. On the Reading Rest 9 March, 2015) exemplify the way real-time archaeological past on a hillock in Uppland link-in with the fictional pan-European alleged time perspective in Beowulf and Codex Regius, it stands to reason that the Spreado hall, like many other halls, was the home of local real-life Hrothgar, Unferth and Beowulf as well as Sigurðr, Guðrún, Gunnarr and Brynhildr loving and hating each other. Although Spreado was a small place — the spiral gold ring buried outside the hall (house 2/21) (Spreado:241, A26) was actually made of gilded copper — there is nevertheless a chance that when Guðrún from Spreado left for Denmark and married Jonakr she went to Dejbjerg on Jutland.

Today, little by little archaeology in Scandinavia excavates both the large halls where the heroic epics were recited as well as the small ones in which the historical events that formed the backbone of the epics took place.

.

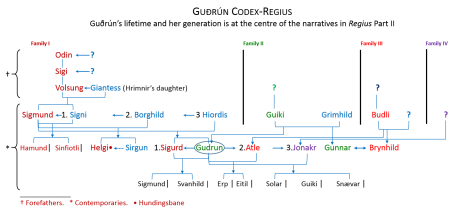

Codex Regius is a Synopsis

9 March, 2015

This week On the Reading Rest I have Codex Regius – well a copy printed from the web: http://www.germanicmythology.com/works/CODEXREGIUS.html

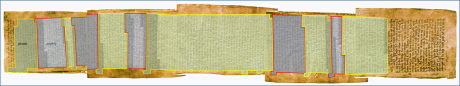

Codex Regius is a manuscript, a compilation of more or less ancient Old Norse texts, mostly poems. In the manuscript, the prose is thought to have been added in the process of compiling the poetry. The actual vellum is a copy of a lost original. Some alterations may nevertheless have been made when the copy was produced. The original collection was based on several different sources and its compilation is dated to the first half of the 13th century CE. Regius dates to the second half. The manuscript consists of two major parts each divided in to two smaller ones and traditionally (in printed editions) it is divided into sections as listed below. Some texts are monologues, mo, some have a prose introduction, pi, others a prose epilogue, pe. Some are pure poetry, some mix prose and poetry and two are just prose.

Codex Regius is a manuscript, a compilation of more or less ancient Old Norse texts, mostly poems. In the manuscript, the prose is thought to have been added in the process of compiling the poetry. The actual vellum is a copy of a lost original. Some alterations may nevertheless have been made when the copy was produced. The original collection was based on several different sources and its compilation is dated to the first half of the 13th century CE. Regius dates to the second half. The manuscript consists of two major parts each divided in to two smaller ones and traditionally (in printed editions) it is divided into sections as listed below. Some texts are monologues, mo, some have a prose introduction, pi, others a prose epilogue, pe. Some are pure poetry, some mix prose and poetry and two are just prose.

Originally the manuscript consisted of 96 or 98 pages, but today only 90 pages remain since there is a lacuna between page 64 and 65. In this lacuna c. 200 or c. 270 lines, i.e. 6 or 8 pages have disappeared. Four pages of a poem in the style of Brot af Sigurðarkviðu, that is, ‘A fragment of the poem about Sigurd’, contain c. 300 poetic long lines or c. 75 strophes. On the 6 or 8 pages that once filled up the lacuna both the end of the poem Sigrdrífomál from strophe 38 and onwards and a ‘long’ Siguðarkviða, except for the last 18.5 strophes, must have got room. We can expect either 100 or 130 strophes to have disappeared in the lacuna, given that part of the pages were probably filled with prose. If we can imagine a Siguðarkviða twice the length of the short one (Sigurðarkviða in skamma) and thus about the same length as Hávamál, then we can imagine that only the end of Sigrdrífomál and major part of The long Siguðarkviða were lost. Be this as it may, the loss would have been part of a group of poems centring on Sigurð, Guðrún, Gunnarr, Brynhildr and their world. This series of poems, the second part of the manuscript starting on page 39, is introduced by the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana I.

Originally the manuscript consisted of 96 or 98 pages, but today only 90 pages remain since there is a lacuna between page 64 and 65. In this lacuna c. 200 or c. 270 lines, i.e. 6 or 8 pages have disappeared. Four pages of a poem in the style of Brot af Sigurðarkviðu, that is, ‘A fragment of the poem about Sigurd’, contain c. 300 poetic long lines or c. 75 strophes. On the 6 or 8 pages that once filled up the lacuna both the end of the poem Sigrdrífomál from strophe 38 and onwards and a ‘long’ Siguðarkviða, except for the last 18.5 strophes, must have got room. We can expect either 100 or 130 strophes to have disappeared in the lacuna, given that part of the pages were probably filled with prose. If we can imagine a Siguðarkviða twice the length of the short one (Sigurðarkviða in skamma) and thus about the same length as Hávamál, then we can imagine that only the end of Sigrdrífomál and major part of The long Siguðarkviða were lost. Be this as it may, the loss would have been part of a group of poems centring on Sigurð, Guðrún, Gunnarr, Brynhildr and their world. This series of poems, the second part of the manuscript starting on page 39, is introduced by the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana I.

It is odd that Codex Regius consists of two components, prose and poetry, rather than just one or the other. Prose is always explanatory or narrative. Direct speech is used in most texts, predominantly in poetry, but even in prose as quotations, quoted strophes or half strophes. In the poetry direct speech occurs in monologues and dialogues. Dialogues may characterize the entire poem or blend with narrative strophes. Dialogues may constitute scenes or they may be used as references. Direct speech is also used when it is not part of a dialogue.

When dialogues are used in scenes, the scenes themselves play a part in the dialogue and the scene is often referred to by those who talk to each other. Stranding in front of her lover Helgi’s mound where the dead Helgi contrary to what she has hoped does not turn up, Sigrún laments: Kominn væri nú ef koma hygði, Sigmundr burr frá sǫlum Óðins—‘he would have come now, if he meant to, Sigmund’s son from Óðinn’s halls’. The strophe explains the situation to us when we see Sigrún by the mound. And it refers to a lost or suppressed dialogue between Sigrún and her maid in which the maid tells her mistress that she had met the dead Helgi and his dead men riding towards his mound. With a great presence of mind the maid had asked him whether what she saw was a delusion or Ragnarök. It was neiher. Formally, when seeing Sigrún by the mound we may wonder where she is and what she is doing. In effect, therefore, the strophe explains something in relation to the dialogue and identifies the mound as Helgi’s rather than one of the other mounds.

Roughly speaking, there are three ways of using dialogue in Eddic poems.

Group I. Dialogue is consistently used in scenes. There may be some explanatory prose lines, half strophes or strophes, e.g. in the beginning of a poem as in Oddrúnargrátr. Prose occurs between the strophes, but it is redundant if the scene is performed. Generally speaking poems in this group have two metrical forms – either A, ljóðahattr or B, fornyrðislag/málaháttr, but meters may also be mixed as in Fáfnismál, or deviant ljóðahattr as in Hárbarzlióð.

Group II. Dialogue is used in scenes within a narrative where direct speech stands out as quotation or explanation. There is also descriptive prose and explanatory strophic poetry. The meter is fornyrðislag/málaháttr except for one strophe in Helgakviða Hundingsbana II (st. 29) and several in Reginsmál, in which ljóðahattr is used. Reginsmál and Fáfnismál is actually one section in the manuscript (page 56:line 30 to page 61:line 19), and Reginsmál, in which there is more prose than poetry, uses strophes from at least two poems, sometimes embedding a strophe in a prose description. Reginsmál pinches together quotations, fragments of scenes and explanatory prose in order to introduce the reader to Fáfnismál, which is dominated by poetry.

Goup III. Narratives that makes use direct speech as quotations. Sometimes the direct speech is organized as dialogues, but not as dramatic scenes in their own right. Dialogues in these poems may be echoes of actual dramatic scenes or composed as referring to fictitious scenes never staged. There is no sharp divide between groups, II and III. The meter used is fornyrðislag as one would expect from a narrative or epic poem.

Goup III. Narratives that makes use direct speech as quotations. Sometimes the direct speech is organized as dialogues, but not as dramatic scenes in their own right. Dialogues in these poems may be echoes of actual dramatic scenes or composed as referring to fictitious scenes never staged. There is no sharp divide between groups, II and III. The meter used is fornyrðislag as one would expect from a narrative or epic poem.

The poems in Codex Regius sort themselves in different ways. Their point of departure is the obvious performative poems i.e. the monologues, designated mo. These poems are followed by the most dialogical and scenic poems, Goup I. The mixed poems, which blend narrative, direct speech, dialogue and scenes, follow suite. One group of mixed poems, Group II, has scenes embedded in descriptions and direct speech. The latter stands out as quotations. The other, Group, III, lacks genuine scenes inasmuch as the dialogues are meant to support a more straightforward narrative. Passages that formally speaking are dialogues or monologues, therefore, stand out as quotations or references.

The poems in Codex Regius sort themselves in different ways. Their point of departure is the obvious performative poems i.e. the monologues, designated mo. These poems are followed by the most dialogical and scenic poems, Goup I. The mixed poems, which blend narrative, direct speech, dialogue and scenes, follow suite. One group of mixed poems, Group II, has scenes embedded in descriptions and direct speech. The latter stands out as quotations. The other, Group, III, lacks genuine scenes inasmuch as the dialogues are meant to support a more straightforward narrative. Passages that formally speaking are dialogues or monologues, therefore, stand out as quotations or references.

In sections which mix poetry and prose (the underlined ones) prose is used either in order to explain something that may actually be inferred from a close reading of the strophes (Fǫr Skirnis and Lokasenna), or it may have been inserted in order to make up for missing parts, i.e. something that cannot be inferred. The beginning of Regius, Part II there are four sections Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, Helgakviða Hiǫrvarzonar, Helgakviða Hundingsbana II and Reginsmál in which one has tried, but not really succeeded, to reconstruct and/or piece together a poem by means of a glue made of prose. Together with the prose section Frá dauða Sinfiǫtla these poems form the introduction to the rest of Regius, Part II. It is their contents rather than their poetic qualities that matters to the compiler.

An instructive example of moderate reconstruction of the contents of lost strophes suggests itself in the poem Vǫlundarkviða between strophe 15 and 18. The manuscript is easy to read and obviously the last part of strophe 15 and most of strophe 16 have not been remembered completely. In order to understand strophe 17 and 18, prose would seem to have been added to make up for what was not readily remembered as poetic strophes.

An instructive example of moderate reconstruction of the contents of lost strophes suggests itself in the poem Vǫlundarkviða between strophe 15 and 18. The manuscript is easy to read and obviously the last part of strophe 15 and most of strophe 16 have not been remembered completely. In order to understand strophe 17 and 18, prose would seem to have been added to make up for what was not readily remembered as poetic strophes.

Looking at Regius as a structured manuscript and at the technical character of its sections, the two main parts I & II stand out as different. Moreover, Regius, Part I is Æsir-centred (from Vǫluspá to Alvissmál) and Part II is Guðrún-centred (from Helgakviða Hundingsbana I to Hamðismál). Each part is marked by specific relations to the future. The Æsir-centred material contains a number text that makes it obvious that ‘now’, when Tyr has lost his hand and Balder is no longer among us, everybody is waiting for the Fimbulwinter and its consequence Ragnarök. Gods, giants and the odd human being are looking towatds inevitable fate looming in a future winter that never ends.

Motives on gold bracteates hint that humans such as Sigrún’s maid may think that this could be a 5th century situation. The Æsir-centred poems are composed for those who were wise after the event.

Motives on gold bracteates hint that humans such as Sigrún’s maid may think that this could be a 5th century situation. The Æsir-centred poems are composed for those who were wise after the event.

*

In the Guðrún-centred Part II, nobody of importance pays heed to imminent Ragnarök let alone its prelude. In fact, living their upper-class pre-Fimbulwinter Miðgard life the upper classes cannt be bothered with catastrophe as long as it doesn’t involve family. Guðrún’s life is a complete failure inasmuch as all her seven children die without having reproduced themselves. Name dropping suggests that Guðrún’s was a pre-Ragnarök dysfunctional ‘lifetime’ involving kings and queens of the kind that played a role in 4th, 5th and 6th century affairs. The poems erre composed to satisfy the curiosity of those who were not involved in days of yore. This means that relatively speaking Regius Part I & II are more or less contemporary and pre-Fimbulwinter.

In the Guðrún-centred Part II, nobody of importance pays heed to imminent Ragnarök let alone its prelude. In fact, living their upper-class pre-Fimbulwinter Miðgard life the upper classes cannt be bothered with catastrophe as long as it doesn’t involve family. Guðrún’s life is a complete failure inasmuch as all her seven children die without having reproduced themselves. Name dropping suggests that Guðrún’s was a pre-Ragnarök dysfunctional ‘lifetime’ involving kings and queens of the kind that played a role in 4th, 5th and 6th century affairs. The poems erre composed to satisfy the curiosity of those who were not involved in days of yore. This means that relatively speaking Regius Part I & II are more or less contemporary and pre-Fimbulwinter.

Gods and members of the upper classes think differently about Ragnarök. Gods are preoccupied by their fate and freak out, the upper classes cannot be bothered as they have their hands full of fighting, loving, hating, and killing each other. Thus the loyalty of the maid is deviant, cleverly seeking information to pass on to her mistress. Sigrún herself couldn’t have asked her lover Helgi whether he had become an illusion or gone Ragnarök, but since her maid knows that Sigrún wants to know she asks the stupid question and gets the reassuring answer.

Codex Regius is not a collection of old verse, it is a composition that aims at compiling a base for describing the trauma and moral dissolution among gods and upper classes in the years leading up to the Fimbulwinter (the cold decade 536-45 CE) and the ensuing Ragnarök. The imminent outcome of these events is known: nearly all gods will die and some humans survive. The audience therefore consists of the progeny of those who survived the decade and populate the new world overseen by surviving goddesses and new gods like Rigr and the resurrected Balder. The audience will not be surprised to hear that in the past the upper classes proved themselves fighting, loving and hating each other in much the same way as they have continued to do after Ragnarök, when society started from scratch although spite and iniquity hadn’t been stamped out.

Obviously, composing poems in the Æsir-centred Part I makes sense only in order to settle the scores. Having done that, this kind of poetry will stand out as a critical conclusion to the era of old gods. This is an interesting genre allowing a poet to compose grotesque works like Lokasenna, but in the long run it will not be as productive as poems concerning the lives of the upper classes, who, accepting the end of the old society, see themselves as ancestors to the old gods as well as survivors of Ragnarök.

Codex Regius, therefore, is a purposeful collection of works compiled to describe the mid-6th c. end of the old society and its gods. The balance between the two parts – Part I being shorter than Part II – suggests that composing poems in the Guðrún-centred genre, digging up the historical roots of the surviving upper classes, was more popular than composing Æsir-centred works. But this is of minor importance in a collection composed to point out a traumatic past rather than collecting old poems. Regius is a collection of material needed and ordered by someone who wanted to write an epic poem about the world that disappeared in the middle to the 6th century. Writing about this period is nothing unique, Beowulf treats the same period albeit from a purely human point of view. Contrary to Regius, people in Beowulf are forced to experience the breakdown of society with little hope of surviving. Beowulf offers a simple explanation: this happens to a society that doesn’t know God! Today we are not convinced, but in Beowulf as well as Regius, we can appreciate their dystopic end in which death signals that nothing but silence remains.

Regius is a collection of texts needed to compose a long poem juxtaposing the harsh fate of the gods and the arrogant recklessness of the horrible old regime. It is easy to see that such a poem could start by criticizing the gods, their appalling behaviour, which helped to bring about catastrophe, and continue focusing on the equally appalling behaviour of the worldly upper classes – a poem about a rotten Ásgard mentality making itself felt in Miðgard. If we want a hero like Beowulf to be the protagonist of the poem we might opt for Skirnir, the Gods’ messanger.

Without really interfering with fate, the story and its digressions, adding some Christian points of view in the simplistic way characteristic of Beowulf could easily explain the cultural breakdown and deranged behaviour referring to the fact that people didn’t know God. In short: we don’t know whether Regius was ever composed as a poem or written down, luckily, however, the compilation lived a literary life of its own.

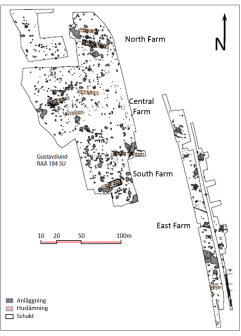

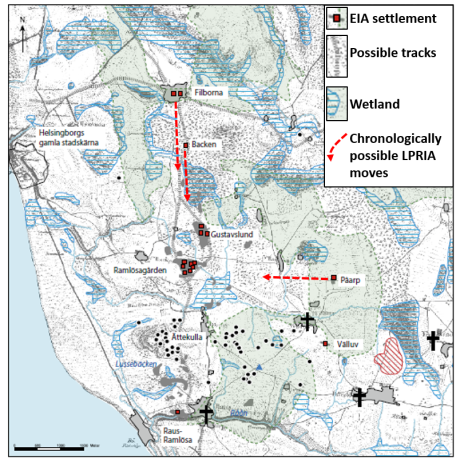

This week On the Reading Rest I have a report in Swedish from a rescue excavation in an urban exploitation area. During the last 10-15 years archaeologists from UV Syd have pieced together the history of a number of Early Iron Age (EIA) villages and farms in the hinterland of historical Helsingborg, One of these is Gustavslund.

Aspeborg, Håkan & Strömberg, Bo. 2014. H. Aspeborg (red.) Gustavslund – en by från äldre järnålder. Skåne, Helsingborgs stad Husensjö 9:25 (Gustavslund), RAÄ 184. UV Rapport 2014:132. Riksantikvarieämbetet. http://samla.raa.se/xmlui/handle/raa/7729?show=full Acronym: HASB

Aspeborg, Håkan & Strömberg, Bo. 2014. H. Aspeborg (red.) Gustavslund – en by från äldre järnålder. Skåne, Helsingborgs stad Husensjö 9:25 (Gustavslund), RAÄ 184. UV Rapport 2014:132. Riksantikvarieämbetet. http://samla.raa.se/xmlui/handle/raa/7729?show=full Acronym: HASB

Today, an area in the outskirts of the town. The present Gustavslund farm (18th c. Mårtenstorp – Martin’s thorp) was founded in 1792 when surveyors established the boundaries of the property and eventually, in 1810, carried out a land consolidation.

By 1810 the EIA settlement area was situated in the grassland at the eastern border of the estate and the westerns border of neighbouring farms. Probably the settlement remains had been invisible and forgotten for more than a millennium. Protected by its peripheral situation in the historical landscape, in itself typical EIA situation, the location of the prehistoric settlement was model – homesteads sitting between two water causes, c. 3 km from Öresund, a little below a flat hilltop, on a slope facing the SW, above a small wetland and brooks suitable for water-meadows – model, but not exceptional. Today, large parts of the settlement area have been excavated accommodating infrastructure, housing and private company offices along a road. This road follows an old N-S divide in the landscape, a parish border as well as the border of Gustavslund. When this zone was made a ring road, Österleden, in the late 20th century no excavations took place at Gustavslund and some parts of the settlement area were damaged prior to the investigations in the early 2000s. The southwestern parts of the settlement have not yet been excavated probably because they are not yet threatened by the growing town.

By 1810 the EIA settlement area was situated in the grassland at the eastern border of the estate and the westerns border of neighbouring farms. Probably the settlement remains had been invisible and forgotten for more than a millennium. Protected by its peripheral situation in the historical landscape, in itself typical EIA situation, the location of the prehistoric settlement was model – homesteads sitting between two water causes, c. 3 km from Öresund, a little below a flat hilltop, on a slope facing the SW, above a small wetland and brooks suitable for water-meadows – model, but not exceptional. Today, large parts of the settlement area have been excavated accommodating infrastructure, housing and private company offices along a road. This road follows an old N-S divide in the landscape, a parish border as well as the border of Gustavslund. When this zone was made a ring road, Österleden, in the late 20th century no excavations took place at Gustavslund and some parts of the settlement area were damaged prior to the investigations in the early 2000s. The southwestern parts of the settlement have not yet been excavated probably because they are not yet threatened by the growing town.

Similar to the excavations at Västerås – the focus of OtRR 6 October 2014, 1 December, 2014 and 3 November, 2014 – once begun by Håkan Aspeborg, HA in the above acronym, the excavations in the outskirts of Helsingborg have been archaeologically most rewarding. And the present report adds considerably to the overall picture.

Similar to the excavations at Västerås – the focus of OtRR 6 October 2014, 1 December, 2014 and 3 November, 2014 – once begun by Håkan Aspeborg, HA in the above acronym, the excavations in the outskirts of Helsingborg have been archaeologically most rewarding. And the present report adds considerably to the overall picture.

HASB has identified four settlement sites – three in the present report and one in an earlier publication (1). They conclude that in the centuries around the beginning of the Common Era the settlement area was a small village consisting of (at least?) four farms and covering c. 400×200 m or 8 ha. This village may be described as a settlement phase in which suitable, but spatially loosely defined sites, which had been used sporadically in the preceding centuries, were now permanently settled for a longer period.

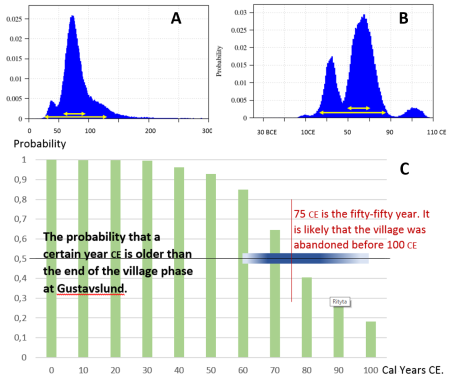

The 14C-dates give a general picture of the chronology of settlement in the area with a strong emphasis on the centuries around the beginning of the Common Era. Precisely dating the beginning of this village period is difficult, owing to the flat calibration curve, but the end of the village phase is less difficult to pinpoint.

Because of the general character of the 14C-dates we may add the ones from the earlier excavations in the eastern part of the village and look at the chronology of the 4-farm village, as HASB do when they sum up Gustavslund (HASB:73-88). The site was used sporadically for hundreds of years before the village was established in the late PRIA and given up in the ERIA. Nevertheless, the area that was once the central part of the village saw stray presence as late as the 5th century CE.

Because of the general character of the 14C-dates we may add the ones from the earlier excavations in the eastern part of the village and look at the chronology of the 4-farm village, as HASB do when they sum up Gustavslund (HASB:73-88). The site was used sporadically for hundreds of years before the village was established in the late PRIA and given up in the ERIA. Nevertheless, the area that was once the central part of the village saw stray presence as late as the 5th century CE.

Analyzing the 14C-tests in Bcal (2), we can date the end of the village relatively sharply, modelling it in three ways. First (A) we may consider that the tests that belong to the last 20 14C-years of the village period represent the end of the settlement. There are six tests dated between 1953 and 1933 bc. Modelling the end of this phase returns the period 31 to 137 CE with a 95% probability and 56 to 94 CE with a 68% probability.

We may also (B) consider that these last six dates represent the same end date and pool them. In that case the pooled date is somewhere between 22 to 85 CE with a 95% probability and 52 to 75 CE with a 68% probability. This analysis neutralizes the probabilities stretching into the 2nd c. CE, induced by the calibration curve, but the basic hypothesis is nevertheless questionable.

Lastly (C), we may ask what the probability is that a certain year is older than the end of the village phase. This analysis returns the most reasonable understanding of the end date – a date in the last half of the first century CE. Method one and two match each other supporting the interpretation that the village was abandoned in the later part of the 1st c. CE. When we know this we may start wondering why it existed for c. 200 years.

One of the main topics discussed by HASB in connection with the EIA settlements around Helsingborg is the production of ceramics during the LPR- and ERIA – the centuries around the beginning of the Common Era (3). Potsherds are abundant on these sites and together with several ovens at Gustavslund as well as nearby Backen and Ramlösagården, they indicate a production in excess of household needs. On the two former sites there was probably no, or very limited, iron production, which means that hearth areas, wells, pit shelters/houses and the odd lump of fine clay are more clearly linked to pottery production.

Since most people made their own, selling ceramics (or for that matter iron tools) in the PRIA was probably not big business. The production therefore begs the question: to whom would the potters at Backen, Gustavslund and Ramlösagården have sold their pots with a profit? And: could the people at Gustavslund pack their wagons and set out on a tour selling ceramics to the coastal population between Halmstad and Malmö competing with their neighbours from Ramlösagården?

The answer is: No! In order for producers or traders to distribute household ware it takes a regionally developed infrastructure, suitable wagons, large scale pottery firing and not least market places where people would buy all kinds of commodities. There is no archaeological evidence for such a complex economic system, investments or power-structured society in the PRIA. Alternatively, bearing in mind the settlement expansion east of today’s Helsingborg, we may argue that in the end of the PRIA pottery production and settlement, such as the 4-farm village Gustavslund, were two sides of the same coin.

The chronological settlement pattern of Gustavslund as well as that of the Backen settlement, 1.5 km North of Gustavslund, are typical: sporadic – concentrated – stray, but also characterized by pottery production in excess of household needs (4).

Nevertheless, Backen and perhaps also Filborna and Påarp (5) were closed down in the first part of the EIA expansion. However, 14C-wise, it would seem that Backen could have been moved to become the North farm in Gustavslund when settlements were concentrated to the village. This is obviously difficult to prove, but is it likely that the seemingly instant foundation of the 4-farm village was not the result of a growth of population, but rather the result of farms (and people) moving to a certain location at a certain point in time. The village was founded and four settlement sites that had been used now and again over the years were permanently settled.

Nevertheless, Backen and perhaps also Filborna and Påarp (5) were closed down in the first part of the EIA expansion. However, 14C-wise, it would seem that Backen could have been moved to become the North farm in Gustavslund when settlements were concentrated to the village. This is obviously difficult to prove, but is it likely that the seemingly instant foundation of the 4-farm village was not the result of a growth of population, but rather the result of farms (and people) moving to a certain location at a certain point in time. The village was founded and four settlement sites that had been used now and again over the years were permanently settled.

This patterns implies a clue to answering the question: to whom did the potters sell their pots? Instead of thinking up an anachronistic economy with markets, transportation and exchange of simple commodities such as pots, it is more rewarding to understand villages such as Gustavslund to be markets in themselves or trade stations where good quality pots are produced and bartered or sold to people who arrive there from the inland to sell their products and as a fringe benefit buy good quality pots difficult to produce in the woodlands. What the trappers would sell is not necessarily sold to the people of Gustavslund, but rather to people who would move valuable the goods out of Scania. Villages such as Gustavslund and Ramlösagården are attractive to trappers, locals and traders, since villages facilitate transhipment and trade as well as the production of pots.

This patterns implies a clue to answering the question: to whom did the potters sell their pots? Instead of thinking up an anachronistic economy with markets, transportation and exchange of simple commodities such as pots, it is more rewarding to understand villages such as Gustavslund to be markets in themselves or trade stations where good quality pots are produced and bartered or sold to people who arrive there from the inland to sell their products and as a fringe benefit buy good quality pots difficult to produce in the woodlands. What the trappers would sell is not necessarily sold to the people of Gustavslund, but rather to people who would move valuable the goods out of Scania. Villages such as Gustavslund and Ramlösagården are attractive to trappers, locals and traders, since villages facilitate transhipment and trade as well as the production of pots.

But is there any indications of inland Scania and Småland being exploited by trappers settled in the inland at this early date? Indirectly there is a find pattern suggesting this.

The low value Roman coins minted in the centuries around the beginning of the Common Era are typical in their distribution (1) in the coastland, (2) the inland and (3) possibly along routes of communication between inland and coastland (cf. OnRR 23 January, 2012). The presence of these coins and their distribution can be explained if we look at them as counters, tokens or IOUs in transactions between, a trader, a trapper and a middlemen. Limited and controlled, as such a system needs to be in order to be fair, it is nevertheless, a system that could turn products such as good quality ceramics (as well as iron tools) into a commodity. In such a system there is a point in concentrating potters and craftsmen in a village, because it will make the village more interesting to those involved in the system. The low-value or, in terms of real metal value, almost worthless Roman coins, have the advantage of being difficult to counterfeit. On the other hand: the closer South Scandinavia gets to Roman economy, the easier the access to low value coins. However, if the introduction of this coinage into the system cannot be controlled, then the system will probably collapse after having been sabotaged by coins that have not been introduced as payment for commodities traded within the system. If this happens, that is, if stakeholders get the feeling that there are more coins in the system than they have agreed, then Roman coins will tend to cause distrust within the systems. Thus enhanced economic activity in EIA society will probably lead to the introduction of weighed bullion as payment, as indeed it does in the LRIA.

The low value Roman coins minted in the centuries around the beginning of the Common Era are typical in their distribution (1) in the coastland, (2) the inland and (3) possibly along routes of communication between inland and coastland (cf. OnRR 23 January, 2012). The presence of these coins and their distribution can be explained if we look at them as counters, tokens or IOUs in transactions between, a trader, a trapper and a middlemen. Limited and controlled, as such a system needs to be in order to be fair, it is nevertheless, a system that could turn products such as good quality ceramics (as well as iron tools) into a commodity. In such a system there is a point in concentrating potters and craftsmen in a village, because it will make the village more interesting to those involved in the system. The low-value or, in terms of real metal value, almost worthless Roman coins, have the advantage of being difficult to counterfeit. On the other hand: the closer South Scandinavia gets to Roman economy, the easier the access to low value coins. However, if the introduction of this coinage into the system cannot be controlled, then the system will probably collapse after having been sabotaged by coins that have not been introduced as payment for commodities traded within the system. If this happens, that is, if stakeholders get the feeling that there are more coins in the system than they have agreed, then Roman coins will tend to cause distrust within the systems. Thus enhanced economic activity in EIA society will probably lead to the introduction of weighed bullion as payment, as indeed it does in the LRIA.

A similar development can be seen in the transition from E- to LCIA. In the 8th century low value coins (sceattas) were minted in Ribe and used with a nominal value on the market – being the coins of this market, which was under some sort of control (6). Nevertheless, in the economic boom of the 9th and 10th c. silver weight economy carried the day in South Scandinavia. In most of the 10th c. Arabic dirhams and fragments down to a quarter were used in market places in order to speed up transaction time without losing track of their real value. They were thought of and represent a certain, small, amount of pure silver. In the end of the 10th c. coins with a nominal value are reintroduced as a royal coinage sometimes strongly linked to a market as in the Swedish case of King Olof Skötkonung and Sigtuna (7) .

To sum up: in a fairly low structured society with a limited power control and little spatial authority, booming economies make it difficult to handle economically sound notions such as nominal values. The reason for this is simple: during a boom transactions cannot be confined to organized markets and production places large enough to create and sustain their own coinage. Instead prices can be negotiated everywhere – not in relation to the commodities of a controlled market, but in relation to the value of a precious metal such as silver.

Owing to initial contacts with the Roman world economy, the economic raison d’être of a potters’ villages as an embryonic production and market place or trade station may well have become a fact. If so access to good clays, skills and local control of power were behind this possibility to satisfy a demand. When these contacts boomed local economic raison d’être disappeared. This change could be expressed in many very different way. That is why we may describe it as the end of the village as well as the ability of trappers, potters and middlemen to organize themselves in inland settlement areas during the prosperous RIA.

NOTES

(1) Aspeborg, Håkan. 2012. Österleden vatten, etapp 2 Skåne, Helsingborgs kommun, Helsingborgs stad, Husensjö 9:25, RAÄ 261. Arkeologisk förundersökning 2011. Uv rapport 2012:31. http://samla.raa.se/xmlui/bitstream/handle/raa/5305/uvr2012_031.pdf?sequence=1

(2) The BCal team comprises Caitlin Buck, Geoff Boden, Andrés Christen, Gary James and Fred Sonnenwald. The URL for the service (http://bcal.sheffield.ac.uk). The paper that launched it was Buck C.E., Christen J.A. and James G.N. 1999. BCal: an on-line Bayesian radiocarbon calibration tool. Internet Archaeology, 7. (http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue7/buck/).

(3) There is a thorough formal analysis of the ceramic from Gustavslund by Thorbjörn Brorsson that analysis adds significantly to the value of the material.

(Brorsson, T. 2014. Den förromerska och romerska keramikens kronologi och funktion – exempel från Gustavslund I Helsingborg. Appendix 8 in HASB:190-222).

In view what will probably be included of her PhD. dissertation, Katarina Botwid has written an innovative preliminary assessment of the ceramic craftsmanship in EIA Gustavslund, with but a short discussion of the empirical basis for the qualitative categorizations of the craft.

(Botwid, K. 2014. Hantverkstolkning av keramik – en undersökning av forntida keramikers hantverksskicklighet, Appendix 9 in HASB:223-246).

(4) Strömberg, Bo. 2011. Österleden etapp 3, Helsingborg. En hantverksgård från äldre järnålder vid Backen, Helsingborg. Fördjupad förundersökning. Skåne, Helsingborgs stad, Husensjö, fornlämning 265. Uv rapport 2011:138.

(5) Larsson, Rolf and Söderberg, Bengt. 2004. Filborna by – Gård och by i ett långt tidsperspektiv. UV SYD Arkeologiska för- och slutundersökningar Rapport 2004:26. http://samla.raa.se/xmlui/handle/raa/3884

Aspeborg, Håkan. 2012. In: H. Aspeborg med bidrag av Nathalie Becker (red). Arkeologisk undersökning. En storgård i Påarp. Skåne, Välluv socken, Påarp 1:12, RAÄ 22 och 43. UV Syd, dokumentation av fältarbetsfasen 2002:1. http://samla.raa.se/xmlui/handle/raa/6217 .

(6) Feveile, Claus. 2008. Series X and coin circulation in Ribe. In: Tony Abramson (ed.) Two Decades of Discovery. Studies in Early Medieval coinage. Vol. 1. Woodbridge. The Boydell Press. Pp 53-66.

(7) Herschend, Frands. 1992. What Olof had in mind. Fornvännen vol. 87. Stockholm. Pp. 19-31.

Aggersborg: The Resilient Village

15 December, 2014

This week On the Reading Rest have the new Aggersborg publication

Roesdahl, Else et al. 2014. Else Roesdahl, Søren Michael Sindbæk, Anne Pedersen and David M. Wilson (eds). Aggersborg: The Viking-Age Settlement & Fortress. Jutland Archaeological Society Publications vol 82. Århus. Acronym A-SaF.

Roesdahl, Else et al. 2014. Else Roesdahl, Søren Michael Sindbæk, Anne Pedersen and David M. Wilson (eds). Aggersborg: The Viking-Age Settlement & Fortress. Jutland Archaeological Society Publications vol 82. Århus. Acronym A-SaF.

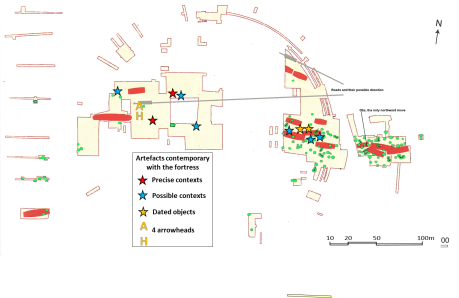

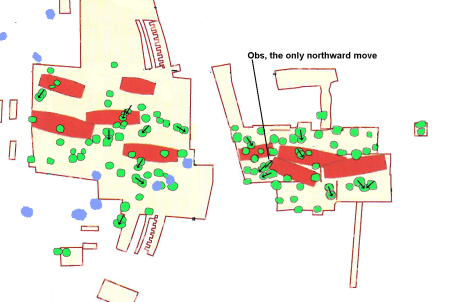

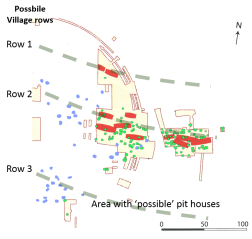

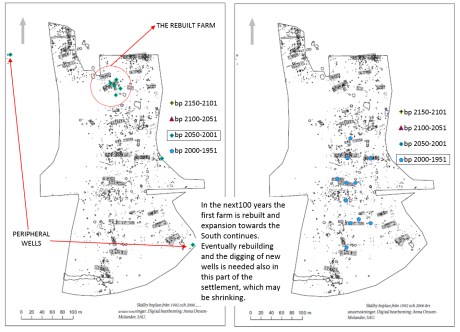

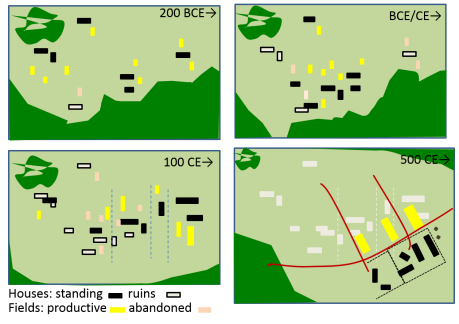

All Aggerborg illustrations in this entry are based on A-SaF.