Late Iron Age Prejudice Act II: ‘Tell me Skírnir what errand have you accomplished in Jotunheim?’

29 October, 2012

This week On the Reading Rest I have a book from which I have taken a general approach to the central part of the poem Skírnismál, i.e. Act II (0).

Brook, Peter. 2011. The Enigmas of Identity. Princeton University Press.

From Peter Brook I borrow two concepts that bracket his analysis and discussion – the initial concepts of ‘Identity’ and ‘identification’ introduced in To Begin and the concluding concepts ‘the Identity paradigm’ and ‘the identificatory paradigm’ introduce in Epilogue: the Identity Paradigm. Peter Brook sees these concepts as emblematic of modern human beings and the ways they experience protagonists, and themselves, through novels, biographies, plays or electoral campaigns. Since Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749) is a first identity case, ‘modern’ refers to the common post Enlightenment-, not least ‘today’-sense, of the term.

From Peter Brook I borrow two concepts that bracket his analysis and discussion – the initial concepts of ‘Identity’ and ‘identification’ introduced in To Begin and the concluding concepts ‘the Identity paradigm’ and ‘the identificatory paradigm’ introduce in Epilogue: the Identity Paradigm. Peter Brook sees these concepts as emblematic of modern human beings and the ways they experience protagonists, and themselves, through novels, biographies, plays or electoral campaigns. Since Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749) is a first identity case, ‘modern’ refers to the common post Enlightenment-, not least ‘today’-sense, of the term.

It may seem odd to apply such a concept when reading an Old Norse poem, but I allow myself to do just that because I think that ‘modern’, rather than signifying the last 250 years of European and North American reality, mirrors an attitude in which the analysis of the present and presence, rather than the past, guides our understanding and manipulation of the future. There is no absolute chronology of ‘the modern’, because the need for modernity is relative.

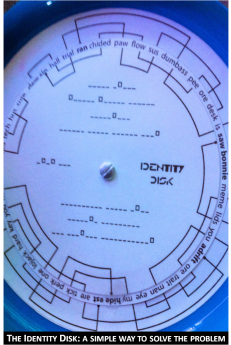

More importantly, I allow myself to adapt Peter Brooks’ view on identity as a notion that evades traditional definition: contrary to being delimited and fixed, identity is a social psychological concept, as basic as the ‘I’, insisting on being changed according to context. When we interrogate individuals trying to define their identity and when we interact with significant others, the identity of all those involved is changed. Despite these insights, our social norms often presuppose the definite identification of someone, and the problem of identity, therefore, stems from the fact that although it is a historical concept, changing during a time series of contexts, it is nevertheless forced now and again to become modern and nothing but present.

Furthermore, I allow myself to think of Peter Brooks’ paradigm turn as the introduction of a non-Kuhnean grammar-like structure that we apply when we want to relate to ourselves and others through fiction.

Furthermore, I allow myself to think of Peter Brooks’ paradigm turn as the introduction of a non-Kuhnean grammar-like structure that we apply when we want to relate to ourselves and others through fiction.

Analyzing Skírnir in Skínismál, the Identity Paradigm becomes important because it prompts the question: who is he and for whom does he woo? And since the poem is critical of the upper classes and their identities it also asks: who are they, the upper classes? The time depth in Skírnismál is ‘a present’, and the possibility that it is set in the present of a once-upon-a-time past, signifies that in itself such a past has nothing to teach us, since it is no more than a present anchored in time. Modernity happens to complicate identity and identification.

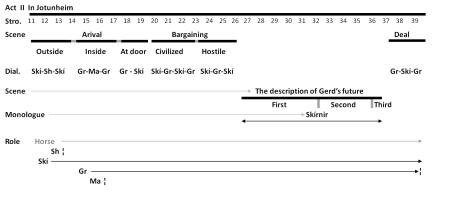

As we read Act II (1) our concerns for Skírnir grows and we wonder about his personal identity, his class identity and whether he can be identified. In act I & II the dialogue technique, using a two- or three-stanza pattern, and the minor characters Skaði, Horse, Shepherd and Maid, are needed to develop the competent character of the protagonist. But when that has been accomplished by the end of verse 16, his personal qualities become a backdrop for his growing incompetence and puzzling identity. And because of his monologue and the way he behaves in Act II, his identity becomes a question that must be resolved.

As we read Act II (1) our concerns for Skírnir grows and we wonder about his personal identity, his class identity and whether he can be identified. In act I & II the dialogue technique, using a two- or three-stanza pattern, and the minor characters Skaði, Horse, Shepherd and Maid, are needed to develop the competent character of the protagonist. But when that has been accomplished by the end of verse 16, his personal qualities become a backdrop for his growing incompetence and puzzling identity. And because of his monologue and the way he behaves in Act II, his identity becomes a question that must be resolved.

If we try to find an answer to Who is he? it will lead us into an infinite regression, structured by a series of Why-is-he? question in pursuit of a non-existent essence in his overpowering present.

When the poet can avail himself of roles and dialogues, i.e. of interaction, the identity of the protagonist, i.e. his complexity, benefits from the scene as a context reflecting identity, and from speech – from expressions related to precise concepts as well as to intentions, norms and structural meaning.

Act I and the beginning of Act II presented us with the role of the competent go-between and we get the impression that Skírnir’s mission is diplomatic. He has come to buy friðr (peace verging on love) and his offer to Gerðr is simple: 11 golden apples! flattering, but essentially ‘Gold’, in return for a straightforward statement from Gerðr saying that to her Freyr is the most un-hated among the living (frið at kaupa, at þú þér Frey kveðir óleiðstan lifa.) – as opposed to the hatred in which gods and giants normally embrace. In effect this means that if Gerðr accepts the offer she is also prepared to let Freyr have his way. Well, she is not, because she detests Freyr and his lot. Gold she has already enough and she’s not afraid to die by Skínir’s sword and besides, what good is a dead Gerðr to Freyr? Friðr, however, is a bit out of place since Freyr is not interested in politics and diplomacy; he is more interested in trafficking. The choice of the diplomatic role is thus wrong and Skírnir’s first fault.

Having come this far into a mock wooing situation we may wonder what’s going on in Skírnir’s mind, and having posed this identity-related question, we might as well go back to the beginning of act II to look for an answer. In so doing we shouldn’t forget that there was a flaw in Skírni’s character visible already in Act I when he called Freyr folkvaldi goða.

The situation is not new to us and we know what the model situation ought to be because Venantius Fortunanus has described it when he wrote a series of poems in connection with the marriage of King Sigebert and Princess Brunhild in Metz 567 CE. Sigebert’s successful Skírnir, in Venantius’ word the ‘serene’ (i.e. Old Norse skír) image of the King, is called Duke Gogo and he brings Brunhild with him back to Metz and Sigebert. We also know from Hêliand (c. 830 CE) that a go-between such as Gabriel may be asked to explain himself well enough for the girl, in his case Mary, to be sure that he is not a fraud. He must prove that God sent him and show his ability to describe the technique and quality of the intercourse, the childbirth and the child. When Gabriel has explained these matters Mary says: ‘after these errends’ meaning now that you have proved yourself as God’s go-between, I am happy to obey. She already knows that she is the ‘maid servant (ambótt) of the folk god’ and her master is obviously entitled to have his his way with her.

The situation is not new to us and we know what the model situation ought to be because Venantius Fortunanus has described it when he wrote a series of poems in connection with the marriage of King Sigebert and Princess Brunhild in Metz 567 CE. Sigebert’s successful Skírnir, in Venantius’ word the ‘serene’ (i.e. Old Norse skír) image of the King, is called Duke Gogo and he brings Brunhild with him back to Metz and Sigebert. We also know from Hêliand (c. 830 CE) that a go-between such as Gabriel may be asked to explain himself well enough for the girl, in his case Mary, to be sure that he is not a fraud. He must prove that God sent him and show his ability to describe the technique and quality of the intercourse, the childbirth and the child. When Gabriel has explained these matters Mary says: ‘after these errends’ meaning now that you have proved yourself as God’s go-between, I am happy to obey. She already knows that she is the ‘maid servant (ambótt) of the folk god’ and her master is obviously entitled to have his his way with her.

The first scene of Act II is an indoor and outdoor situation. It starts outside the farm, goes on to incorporate those indoors and ends up bringing together Gredr and Skírnis when Gerðr tells her maid to invite him into the hall. Gerðr is thus just about to show her good manners offering Skírnir something to drink now that he has come to visit her. Like Mary she is alone.

The first scene of Act II is an indoor and outdoor situation. It starts outside the farm, goes on to incorporate those indoors and ends up bringing together Gredr and Skírnis when Gerðr tells her maid to invite him into the hall. Gerðr is thus just about to show her good manners offering Skírnir something to drink now that he has come to visit her. Like Mary she is alone.

In the first dialogue, verses 11 to 13, Skírnir addresses the Shepherd asking him relatively politely whether he can speak to Gerðr. But despite his good manners, he also indicates that the Shepherd, instead of sitting on his mound keeping watch in all directions, ought to keep the dogs at bay. In principle the shepherd answers: No you can’t! but in practice being a servant or thrall at an Iron Age manor he is not just rude, he also expresses himself pointlessly and badly. He drops a line in the meter and produces the following full line: annspillis vanr þú skalt æ vera, in which we hear an irregular too stressed and well-sounding alliteration between vanr and vera, i.e. between the second and the fourth (sic!) accent. I his first line, moreover, the shepherd repeats ertu unnecessarily: Hvárt ertu feigr, eða ertu framgenginn? Thus creating no less than four unaccented syllables in two similar trochaic words – e’ða e’rtu. This is an exaggeration in the poetic style of the poem. Moreover, ertu feigr and ertu fremgenginn means the same: Are you dead? To answer the question ‘can I speak to your mistress?’ with ‘are you dead or are you dead?’ is not very sophisticated, not least because Skírnir, who started the conversation, is entitled to get the last word. It may well be that the shepperd is genuinly surprised that Skírnir has mananged to travel to Jotunheimen, but even in that case the shepperd is naïve. As Skírnir is upper-class he doesn’t bother to discuss with the shepherd. Instead he indulges in a small homily: ‘For those who have set out on a journey there are better thing to try than being wretched: Down to a day, my time is meted out and the whole of my life determined’. Here endeth the lesson telling the shepherd that to the Late Iron Age upper class male, the journey is the way of fulfilling a task as well as finding an identity and a destiny. Sitting on the mound like a wretched shepherd keeping watch is pointless. This type of conversation is standard, but here it backfires as soon as we understand that the shepherd’s mood is comparable to Freyr’s – the opposite of a folkvaldi goða. Is the Shepherd the wretched Freyr waiting for Skírnir to arrive? Is Freyr Skírnir’s shadow falling upon the shepherd, and Skírnir the serene side of Freyr?

In the first dialogue, verses 11 to 13, Skírnir addresses the Shepherd asking him relatively politely whether he can speak to Gerðr. But despite his good manners, he also indicates that the Shepherd, instead of sitting on his mound keeping watch in all directions, ought to keep the dogs at bay. In principle the shepherd answers: No you can’t! but in practice being a servant or thrall at an Iron Age manor he is not just rude, he also expresses himself pointlessly and badly. He drops a line in the meter and produces the following full line: annspillis vanr þú skalt æ vera, in which we hear an irregular too stressed and well-sounding alliteration between vanr and vera, i.e. between the second and the fourth (sic!) accent. I his first line, moreover, the shepherd repeats ertu unnecessarily: Hvárt ertu feigr, eða ertu framgenginn? Thus creating no less than four unaccented syllables in two similar trochaic words – e’ða e’rtu. This is an exaggeration in the poetic style of the poem. Moreover, ertu feigr and ertu fremgenginn means the same: Are you dead? To answer the question ‘can I speak to your mistress?’ with ‘are you dead or are you dead?’ is not very sophisticated, not least because Skírnir, who started the conversation, is entitled to get the last word. It may well be that the shepperd is genuinly surprised that Skírnir has mananged to travel to Jotunheimen, but even in that case the shepperd is naïve. As Skírnir is upper-class he doesn’t bother to discuss with the shepherd. Instead he indulges in a small homily: ‘For those who have set out on a journey there are better thing to try than being wretched: Down to a day, my time is meted out and the whole of my life determined’. Here endeth the lesson telling the shepherd that to the Late Iron Age upper class male, the journey is the way of fulfilling a task as well as finding an identity and a destiny. Sitting on the mound like a wretched shepherd keeping watch is pointless. This type of conversation is standard, but here it backfires as soon as we understand that the shepherd’s mood is comparable to Freyr’s – the opposite of a folkvaldi goða. Is the Shepherd the wretched Freyr waiting for Skírnir to arrive? Is Freyr Skírnir’s shadow falling upon the shepherd, and Skírnir the serene side of Freyr?

Obviously the Late Iron Age upper classes, represented by Skírnir, treat the lower classes in an appalling way, unable to seeing them as peers and unable to grasp that the feelings of shepherds are on par with their own.

In an equally typical way we understand that two different things are going on when we listen to the dialogue between Gerðr and her maid. They are indoors, but instead of hearing the Shepherd and Skírnir talking to each other, Gerðr hears a ground- and house-shaking noise. Her maid on the other hand tells her about Skírnir and his horse. Similar to the beginning of the Finnsburg fragment, what sounds straightforward to common people is something exceptional to the upper classes. This is when Gerðr sends out the maid to invite Skírnir into the hall and it stands to reason that in his homily Gerðr heard the conviction of the man who asks to see her. She draws the conclusion that she is visited by a super natural Iron Age being and by trouble. But she invites him in, meets him at the door, asks if he is one of the Elfs, Vanir or Æsir and why he has come alone (She doesn’t give a pompous speech about fate and life and she asks because she is Mary-like, she wants to know more, while he is Gabriel-like). Skírnir says that he is neither, but nevertheless coming alone. Perhaps he is just a man, but since he represents the divine, and keeps his identity a secret, he is not completely truthful and we may wonder because he is falling out of the Gogo-Gabriel part. When Gabriel met Mary in Hêliand (in the 830s CE) he was in the same situation, but he revealed his identity and persuaded Mary that he was trustworthy. And duke Gogo who was sent out by King Sigebert to Brunhild in Toledo as his wooer played with open cards in Venantius Fortunatus poems about the marriage of Sigebert and Brunhild (567 CE). Although modelled on the holy wedding, the hieros gamos, theirs was completely a worldly one. Perhaps there is too much Freyr present in Skírnir.

In the next scene we are given some insight into the way the upper classes quarrel. They do it in a progressive Strindbergian fashion starting from a preunderstanding of the situation – not by saying: Are you dead or are you dead?

In the next scene we are given some insight into the way the upper classes quarrel. They do it in a progressive Strindbergian fashion starting from a preunderstanding of the situation – not by saying: Are you dead or are you dead?

Since Skírnir turned Gerðr’s greeting and question into his own enigmatic and negative answer (vv 17 & 18), Gerðr repeats his offers to her in the negative (vv 19&20; 21&22), but each time she develops her response with her own arguments. This obviously irritates Skírnir, who starts threatening to kill her and Gerðr answers that she thinks that her father will anyway fight with Skírnir if they meet (vv 23&24). She could of course have said: Down to a day, my time is meted out … …, but she doesn’t. To the brave, such as Gerðr, death in itself is not a problem as longs as there’s someone to avenge you.

To underscore her disinterest in the matter Gerðr doesn’t end her strophe with a full line which brings things to a close. Instead she prefers the openness of long line when she expresses her presumption. Skírnir doesn’t hesitate to tell her that he will kill her father (v 25) and that brings the dialogue (vv23-25) to a hiatus. Predictably, since killing Gerðr and her father doesn’t solve his problems, Skírnir’s rage grows and his character and thus his identity takes yet a turn. This is the immediate reason why he starts to describe the fate of emancipated and stubborn girls who oppose the way marriage is arranged and negotiated among the LIA upper classes. Shrews lose their identity.

This scene, vv 26 to 31, is also the one in which Skírnir loses his grip on the meter and starts to fill-up the strophes with free-standing repetitive half lines. Modern translators and editors, but not good old Neckel, foolishly indicate some missing lines trying to save Skírnir’s poetical reputation. But in vain. It cannot be helped: unpolished shepherd’s poesy (his Freyr side?) is forcing its way out of his mouth when he projects Freyr’s sentiments on Gerðr’s fate.

This scene, vv 26 to 31, is also the one in which Skírnir loses his grip on the meter and starts to fill-up the strophes with free-standing repetitive half lines. Modern translators and editors, but not good old Neckel, foolishly indicate some missing lines trying to save Skírnir’s poetical reputation. But in vain. It cannot be helped: unpolished shepherd’s poesy (his Freyr side?) is forcing its way out of his mouth when he projects Freyr’s sentiments on Gerðr’s fate.

The scene is cunningly constructed. Once again there are two scenes in one – the quarrelling couple in front of us and Gerðr’s future life subsiding in the quarrel. To make is possible for both to see both realities at one and the same time Skírnir uses a staff, a light one, which intimidates Gerðr. He ‘tames’ her and it pleases him to force her into silence.

The future described in this and the next scene is a decade in the life of a young woman, i.e. Gerðr’s next ten years. Skírnir starts by depicting the not too uncommon teenage girl who turns her back to the world and stops eating because food is disgusting. Naturally she sits looking towards Hell, as worthless people do. Others start staring at her as if she was a lunatic and she becomes famous for being what she has become. Since she is stubborn she is captured by the trolls and starts to live a horrible life for a while before she must choose between one with three heads or never marry. Indirectly we understand that she refuses and that gives the author the possibility to make use of a metaphor from the life of the housewife that she refuses to become to show us how Gerðr, refusing to marry the three-headed troll, is thrown out of society: ver þú sem þistill, sá er var þrunginn i onn ofvanverða—be you like the thistle that which was crowded together in the worthless harvest. The scene refers to the indoor cleansing of the harvest, a daily occupation in the Iron Age household supervised by the housewife. The cleansing divides harvest into three: food for humans, food for animals and waste. The point is that Gerðr, refusing to begome the housewife, is thrown out as the most worthless part of the harvest, the thistles that not even the animals should eat. Being thistle-minded Gerðr has sorted out herself.

Because of her refusal to abate, Skírnir goes on in the next two scenes vv.32-37 to describe her as an exploited woman haunted by her multiple and conflicting identity. His method to achieve this future will be a new staff, which he will use three times on her. To find this staff he shall have to go to the woods and before he leaves Gerðr alone he therefore tells everybody that inasmush as Gerðr has offended the Æsir, Freyr will hate her and Oðinn is angry. Skírnir speaks on his behalf, having twisted his identity once again. To show her the powers invested in him, Skírnir tells Gerðr that with his staff he can force salaciousness, furiousness and impatience, ergi, œði and óþola, upon her as best he pleases. This means that her eventual owner Rimgrimmir doesn’t need to force himself upon her, Gerðr will disgrace herself. Since Skírnir hob nobs with the divine echelons of the LIA society, this is no more than we expect from human beings loyally serving the upper classes.

At this moment Gerðr interrupts Skírnir. She does so because Skírnir has revealed his errand and identity – in reality he is the spokesman of the Æsir and Oðinn. Skírnir’s behavior proves that he is the Æsir’s errand boy. Similar to the way Mary was turned into obedience in Hêliand when Gabriel proved to her that it was the Lord, to whom she was but a servant, who wanted to overcome her with his wonderful shadow from the meadows of Heaven and have some sort of intercourse with her, Gerðr doesn’t object to Oðinn’s will. Gerðr and Mary are not the kind of women who object to the supreme authority, but well to pointless men. As Mary puts it: ‘Now that I know his will, I am his servant’, and so is Gerðr. If the Æsir, i.e. Oðinn, wants her to have intercourse with Freyr then that is OK with Gerðr, and she proposes the rendezvous at Barri. This satisfies Skírnir and perhaps Oðinn, but obviously not Freyr.

In verse 37 Gerðr interrupts Skírnir in a friendly and humorous way. Technically speaking she interrupts his never-ending monologue by greeting him the way she would have done in verse 19, if Skírnir hadn’t lost it: ‘Now you better be welcome young man and take a cup full of old mead’, and then she goes on joking about her situation: ‘That I had thought, though, that I would never make love to the off-spring of Vanir’. Since Skírnir’s mind is still exercising staffs of ergi, œði and óþola she baffles him and he loses face, but manages to be pompously formal: ‘Concerning my mission I want to know, before I leave and ride home, when and where you will give yourself to Njarðr’s dilating son’—nær þú á þingi / munt inom þroska // nenna Njarðar syni‘. If Skírnir had read Hêliand he would have known that part of his role was to describe the quality of the intercourse, albeit in less direct words. He should also have told Gerðr about Oðinn from the very beginning (and said something about the child). But then again, it is difficult to be involved with the divine. This too shows in a subtle way in the verses. In his last demand, Skírnir happens to put þroska in the wrong place, alliterating þingi – þroska on the second and fourth accent. This is odd, but it may of course happen if you are a stressed civil servant and a human being, however clever, among gods and giants. In Corpus Poeticum Boreale (1883) the editors were so embarrassed that they felt the need to ‘corrected’ the line: nær þú á þingi munt / inom þroskamikla.

In verse 37 Gerðr interrupts Skírnir in a friendly and humorous way. Technically speaking she interrupts his never-ending monologue by greeting him the way she would have done in verse 19, if Skírnir hadn’t lost it: ‘Now you better be welcome young man and take a cup full of old mead’, and then she goes on joking about her situation: ‘That I had thought, though, that I would never make love to the off-spring of Vanir’. Since Skírnir’s mind is still exercising staffs of ergi, œði and óþola she baffles him and he loses face, but manages to be pompously formal: ‘Concerning my mission I want to know, before I leave and ride home, when and where you will give yourself to Njarðr’s dilating son’—nær þú á þingi / munt inom þroska // nenna Njarðar syni‘. If Skírnir had read Hêliand he would have known that part of his role was to describe the quality of the intercourse, albeit in less direct words. He should also have told Gerðr about Oðinn from the very beginning (and said something about the child). But then again, it is difficult to be involved with the divine. This too shows in a subtle way in the verses. In his last demand, Skírnir happens to put þroska in the wrong place, alliterating þingi – þroska on the second and fourth accent. This is odd, but it may of course happen if you are a stressed civil servant and a human being, however clever, among gods and giants. In Corpus Poeticum Boreale (1883) the editors were so embarrassed that they felt the need to ‘corrected’ the line: nær þú á þingi munt / inom þroskamikla.

Since the matter at stake is sanctioned by Oðinn, Gerðr tells Skírnir about Barri and since they both know the place, she incorporates a well-known and simple future into Skírnir’s troubled present. This fools him. She closes the case probably as a modern mariage case rather than a case of old-fashioned fertility cult, and Skírnir forgets that he was supposed to bring her home to Ásgard. He could have waited nine days and escorted Gerðr, but didn’t. The fact that the traficking wasn’t successful explains Freyr’s question about the errand.

In the end there is no much left of the competent valet; in fact so is little left that paraphrasing Philip Larkin is the only way to describe Skírnir’s situation:

They fuck you up, your giant gods.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they have

And add some extra, just for you.

But the again he got the sword, and perhaps the horse, didn’t he?

Having read Skírnismál we are able to judge the representatives of any semi-divine LIA King or lord and criticize the inflated and rotten hall-governed upper-class LIA society.

NOTES

______________

(0) Since the text is more important when dealing with Skírnismál Act II, Gudni Jonsson’s commented edtion from 1949 may be of some help. See: http://www.alarichall.org.uk/teaching/skirnismal.pdf

(1) Terry Gunnell in his book The origins of drama in Scandinavia (1995) argued that Skírnismál and other Eddic dialogue poems were plays. I follow in his foot steps.